The recent climate finance agreement reached at Cop29 has faced significant backlash from negotiators representing developing nations. Despite the pledge to increase financial support to poorer countries, voices from the global south have decried the deal as insufficient and reflective of unequal power dynamics.

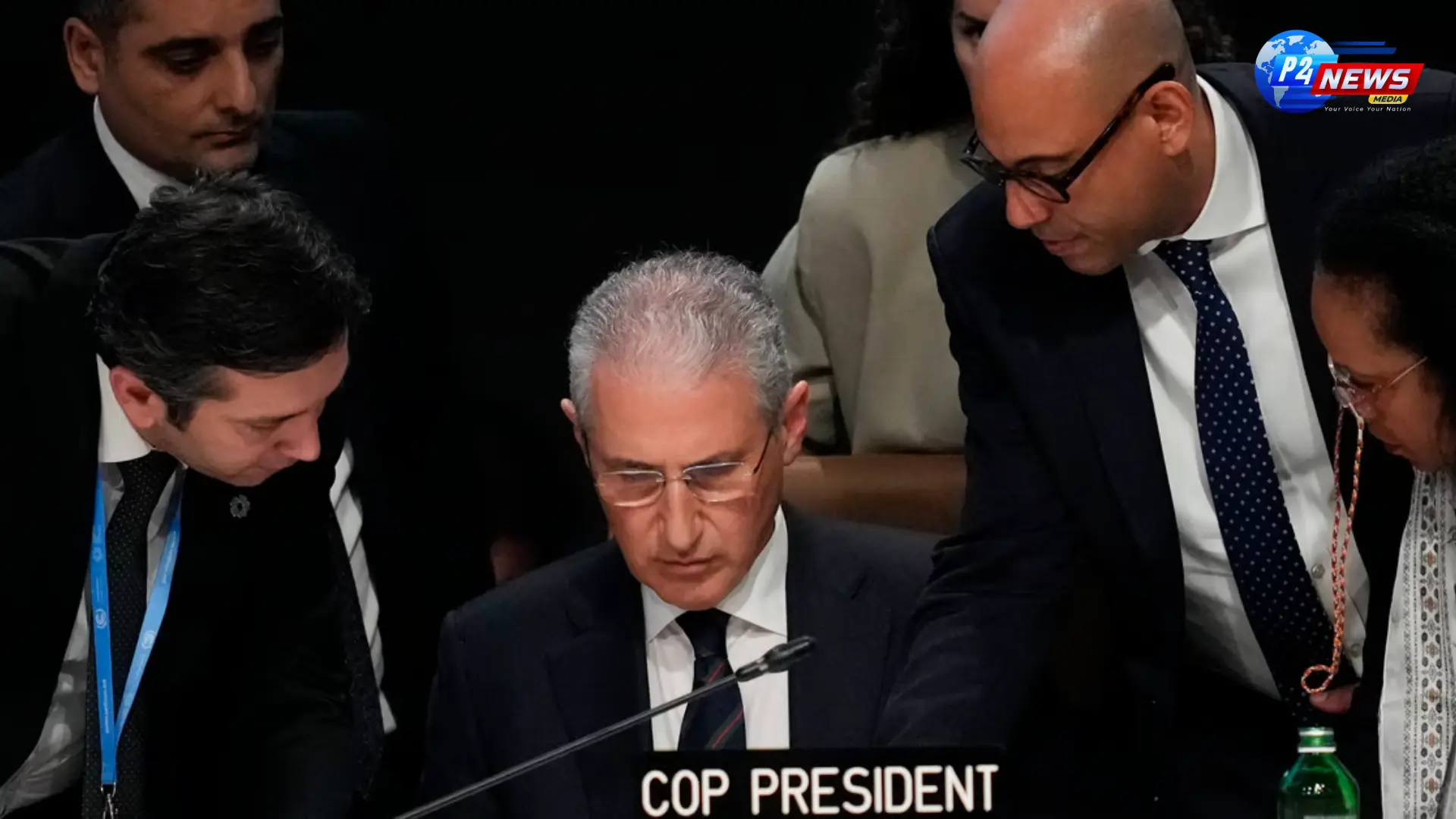

The climate finance agreement finalized during Cop29 has drawn sharp criticism from multiple countries, with negotiators describing it as nothing short of a “travesty of justice.” The conference, which culminated in the early hours of Sunday, saw negotiators agree to a commitment to significantly boost climate financing directed at developing nations. However, the reality falls far short of expectations, leaving many feeling dissatisfied with the final outcome. Developing countries had advocated for a substantial annual assistance of $1.3 trillion to foster decarbonization and mitigate the adverse effects of climate change. The actual deal, however, pledges a mere $300 billion each year, setting a target of $1.3 trillion that appears excessively optimistic given the challenges at hand.

Chandni Raina, a negotiator representing India, did not mince words in expressing her disappointment, labeling the agreement as “abysmally poor.” Raina, who serves as an adviser to the Indian Department of Economic Affairs, underscored the inadequacy of the agreement in addressing the severe climate challenges confronting nations globally. The criticism extended beyond the monetary figures involved; Raina voiced concerns regarding the manner in which the deal was orchestrated.

In the hours leading up to the agreement’s announcement, a select group of delegates from the U.S., Colombia, and several African nations were seen conferring privately over drafts of documents, leading to speculation about procedural irregularities. Raina asserted that such behind-the-scenes negotiations contradicted the spirit of consensus decision-making that the UN climate change framework purports to uphold. Shockingly, India intended to voice its opposition to the deal but found that opportunity summarily denied.

Raina characterized the $300 billion commitment as “stage-managed,” casting doubt on its legitimacy and urging that the situation was akin to an “optical illusion.” Later, in her interview with the Guardian, she reiterated that the adoption of such a meager goal was wholly unacceptable, driving home her conviction that the proceedings at Cop29 were fundamentally unjust.

Moreover, the Cop29 presidency refrained from advancing another pivotal item known as the UAE dialogue, which was intended to build upon a commitment established during the previous summit to phase out fossil fuels. Raina argued that the climate finance issue deserved similar scrutiny and proposed that further clarification was warranted regarding its legal implications.

Critics from various nations echoed Raina’s sentiments, expressing outrage over what they deemed inadequate support for developing regions. A delegate from Nigeria remarked that the notion of developed countries championing a commitment of $300 billion by 2035 was laughable, emphasizing that nations like Nigeria would require significantly more assistance to adequately curb emissions.

Panama's representative for climate change, Juan Carlos Monterrey Gómez, articulated similar concerns, lamenting the speed with which the procedure unfolded and the lack of consideration for nations' voices in the decision-making process. He highlighted a recurring frustration where developed nations present last-minute text adjustments that leave developing countries cornered into compliance under the specter of urgent climate negotiations.

In a poignant moment, delegations representing small island nations and the least developed countries walked out of a meeting in protest, voicing their frustrations over the neglect of their climate finance needs. The least developed countries negotiating bloc, encompassing 45 nations, issued a statement expressing dismay at what they perceived as a callous disregard for years of collaborative effort in shaping the climate finance goal.

Despite the challenges posed by the current geopolitical landscape, some experts like Avinash Persaud recognized the difficult nature of the negotiations, acknowledging that the achieved $300 billion annual target reflects a compromise that balances political feasibility with the urgent needs of developing countries. However, Raina contended that additional safeguards for all developing nations were sorely lacking, insisting that every country should have access to necessary funding.

In conclusion, while some experts remain hopeful that the Cop29 finance agreement signifies at least some degree of progress, others view it as a missed opportunity to rectify systemic inequalities in international climate negotiations. As the world grapples with increasingly dire climate realities, only time will tell whether this agreement will catalyze substantial change or simply perpetuate existing grievances within the global community.

'

Comments 0